How Bitcoin Protects Americans from Inflation

The original cryptocurrency can improve the financial security of hourly wage earners and retirees on fixed incomes.

To younger Americans, digital money is as intuitive as digital media and digital friendships. But Millennials with smartphones are not the only people interested in bitcoin; a growing number of investors are also flocking to the currency’s banner. Surveys indicate that as many as 21% of U.S. hedge funds now own bitcoin in some form. In 2020, after considering various asset classes like stocks, bonds, gold, and foreign currencies, celebrated hedge-fund manager Paul Tudor Jones asked, “What will be the winner in ten years’ time?” His answer: “My bet is it will be bitcoin.”

What’s driving this increased interest in a form of currency invented in 2008? The answer comes from former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, who once noted, “the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press…that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation…the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to…inflation.” In other words, governments with fiat currencies — including the United States — have the power to expand the quantity of those currencies. If they choose to do so, they risk inflating the prices of necessities like food, gas, and housing.

In recent months, consumers have experienced higher price inflation than they have seen in decades. A major reason for the increases is that central bankers around the world — including those at the Federal Reserve — sought to compensate for COVID-19 lockdowns with dramatic monetary inflation. As a result, nearly $4 trillion in newly printed dollars, euros, and yen found their way from central banks into the coffers of global financial institutions.

Jerome Powell, the current Federal Reserve chairman, insists that 2021’s inflation trends are “transitory.” He may be right in the near term. But for the foreseeable future, inflation will be a profound and inescapable challenge for America due to a single factor: the rapidly expanding federal debt, increasingly financed by the Fed’s printing press.

In time, policymakers will face a Solomonic choice: either protect Americans from inflation, or protect the government’s ability to engage in deficit spending. It will become impossible to do both. Over time, this compounding problem will escalate the importance of Bitcoin.

Purchasing Power of the U.S. Dollar, Relative to 1948

(Shaded areas indicate recessions)

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, NBER

Graphic: Avik Roy

The 50-year-old fiat currency experiment

It’s becoming clear that Bitcoin is not merely a passing fad, but a significant innovation with potentially serious implications for the future of investment and global finance. To understand those implications, we must first examine the recent history of the primary instrument that bitcoin was invented to challenge: the American dollar.

Toward the end of World War II, in an agreement hashed out by 44 Allied countries in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, the value of the U.S. dollar was formally fixed to 1/35th of the price of an ounce of gold. Other countries’ currencies, such as the British pound and the French franc, were in turn pegged to the dollar, making the dollar the world’s official reserve currency.

As Jeffrey Garten details in Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy, these exchange rates became increasingly unstable in the decades after World War II. The rising prosperity of Japan and West Germany meant that those countries were receiving U.S. dollars in exchange for their goods and services. Irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies by the Johnson and Nixon administrations increased the amount of dollars owed foreign governments, and also the quantity of dollars in circulation. By the summer of 1971, foreign central banks and governments held $64 billion worth of claims on the $10 billion of gold still held by the United States.

It wasn’t long before the world took notice of the shortage. In a classic bank-run scenario, anxious European governments began racing to redeem dollars for American-held gold before the Fed ran out. In July 1971, Switzerland withdrew $50 million in bullion from U.S. vaults. In August, France sent a destroyer to escort $191 million of its gold back from the New York Federal Reserve. Britain put in a request for $3 billion shortly thereafter.

Finally, that same month, Nixon secretly gathered a small group of trusted advisors at Camp David to devise a plan to avoid the imminent wipeout of U.S. gold vaults and the subsequent collapse of the international economy. There, they settled on a radical course of action.

On the evening of August 15, 1971, in a televised address to the nation, Nixon announced a suspension — eventually, a permanent one — of the right of foreign governments to exchange their dollars for U.S. gold.

Knowing that his unilateral abrogation of agreements involving dozens of countries would come as a shock to world leaders and the American people, Nixon labored to re-assure viewers that the change would not unsettle global markets. He promised viewers that “the effect of this action…will be to stabilize the dollar,” and that the “dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today.” The next day, the stock market rose — to everyone’s relief. The editors of the New York Times “unhesitatingly applaud[ed] the boldness” of Nixon’s move. Economic growth remained strong for months after the shift, and the following year Nixon was re-elected in a landslide, winning 49 states in the Electoral College and 61% of the popular vote.

Nixon’s short-term success was a mirage, however. After the election, the president lifted the wage and price controls, and inflation returned with a vengeance. By December 1980, the dollar had lost more than half the purchasing power it had back in June 1971 on a consumer-price basis. In relation to gold, the price of the dollar collapsed — from 1/35th to 1/627th of a troy ounce. Though Jimmy Carter is often blamed for the Great Inflation of the late 1970s, “the truth,” as former National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow has argued, “is that the president who unleashed double-digit inflation was Richard Nixon.”

Wages as a Share of Gross Domestic Income

(1948–2020; shaded areas indicate recessions)

Departure from the Bretton Woods agreement increased wealth inequality. After 1971, monetary inflation increased the wealth of the U.S. financial sector far greater than for ordinary wage-earners, as illustrated by the share of gross domestic income that derives from compensation of employees. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

In 1981, Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker raised the federal-funds rate — a key interest-rate benchmark — to 19%. A deep recession ensued, but inflation ceased, and the U.S. embarked on a multi-decade period of robust growth, low unemployment, and low consumer-price inflation. As a result, few are nostalgic for the days of Bretton Woods or the gold-standard era. The view of today’s economic establishment is that the present system works well, that gold standards are inherently unstable, and that advocates of gold’s return are eccentric cranks.

Nevertheless, it’s important to remember that the post-Bretton Woods era — in which the supply of government currencies can be expanded or contracted by fiat — is only 50 years old. To those of us born after 1971, it might appear as if there is nothing abnormal about the way money works today. When viewed through the lens of human history, however, free-floating global exchange rates remain an unprecedented economic experiment — with one critical flaw.

An intrinsic attribute of the post-Bretton Woods system is that it enables deficit spending. Under a gold standard or peg, countries are unable to run large budget deficits without draining their gold reserves. Nixon’s 1971 crisis is far from the only example; deficit spending during and after World War I, for instance, caused economic dislocation in numerous European countries — especially Germany — because governments needed to use their shrinking gold reserves to finance their war debts.

These days, by contrast, it is relatively easy for the United States to run chronic deficits. Today’s federal debt of almost $29 trillion — up from $10 trillion in 2008 and $2.4 trillion in 1984 — is financed in part by U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, on which lenders to the United States collect a form of interest. Yields on Treasury bonds are denominated in dollars, but since dollars are no longer redeemable for gold, these bonds are backed solely by the “full faith and credit of the United States.”

Declining faith in U.S. credit

Interest rates on U.S. Treasury bonds have remained low, which many people take to mean that the creditworthiness of the United States remains healthy. Just as creditworthy consumers enjoy lower interest rates on their mortgages and credit cards, creditworthy countries typically enjoy lower rates on the bonds they issue.

Consequently, the post-Great Recession era of low inflation and near-zero interest rates led many on the left to argue that the old rules no longer apply, and that concerns regarding deficits are obsolete. Supporters of this view point to the massive stimulus packages passed under presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden that, in total, increased the federal deficit and debt by $4.6 trillion without affecting the government’s ability to borrow.

The extreme version of the new “deficits don’t matter” narrative comes from the advocates of what has come to be called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), who claim that because the United States controls its own currency, the federal government has infinite power to increase deficits and the debt without consequence. Though most mainstream economists dismiss MMT as unworkable and even dangerous, policymakers appear to be legislating with MMT’s assumptions in mind. A new generation of Democratic economic advisors has pushed President Biden to propose an additional $3.5 trillion in spending, on top of the $4.6 trillion spent on Covid-19 relief and the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill. These Democrats, along with a new breed of populist Republicans, dismiss the concerns of older economists who fear that exploding deficits risk a return to the economy of the 1970s, complete with high inflation, high interest rates, and high unemployment.

But there are several reasons to believe that America’s fiscal profligacy cannot go on forever. The most important reason is the unanimous judgment of history: In every country and in every era, runaway deficits and skyrocketing debt have ended in economic stagnation or ruin.

Another reason has to do with the unusual confluence of events that has enabled the United States to finance its rising debts at such low interest rates over the past few decades — a confluence that Bitcoin may play a role in ending.

Treasury bonds are no longer ‘risk-free’

To members of the financial community, U.S. Treasury bonds are considered “risk-free” assets. That is to say, while many investments entail risk — a company can go bankrupt, for example, thereby wiping out the value of its stock — Treasury bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. Since people believe the United States will not default on its obligations, lending money to the U.S. government — buying Treasury bonds that effectively pay the holder an interest rate — is considered a risk-free investment.

The definition of Treasury bonds as “risk-free” is not merely by reputation, but also by regulation. Since 1988, the Switzerland-based Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has sponsored a series of accords among central bankers from financially significant countries. These accords were designed to create global standards for the capital held by banks such that they carry a sufficient proportion of low-risk and risk-free assets. The well-intentioned goal of these standards was to ensure that banks don’t fail when markets go down, as they did in 2008.

The current version of the Basel Accords, known as “Basel III,” assigns zero risk to U.S. Treasury bonds. Under Basel III’s formula, then, every major bank in the world is effectively rewarded for holding these bonds instead of other assets. This artificially inflates demand for the bonds and enables the United States to borrow at lower rates than other countries.

The United States also benefits from the heft of its economy as well as the size of its debt. Since America is the world’s most indebted country in absolute terms, the market for U.S. Treasury bonds is the largest and most liquid such market in the world. Liquid markets matter a great deal to major investors: A large financial institution or government with hundreds of billions (or more) of a given currency on its balance sheet cares about being able to buy and sell assets while minimizing the impact of such actions on the trading price. There are no alternative low-risk assets one can trade at the scale of Treasury bonds.

The status of such bonds as risk-free assets — and in turn, America’s ability to borrow the money necessary to fund its ballooning expenditures — depends on investors’ confidence in America’s creditworthiness. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve’s interference in the markets for Treasury bonds have obscured our ability to determine whether financial institutions view the U.S. fiscal situation with confidence.

In the 1990s, Bill Clinton’s advisors prioritized reducing the deficit, largely out of a concern that Treasury-bond “vigilantes” — investors who protest a government’s expansionary fiscal or monetary policy by aggressively selling bonds, which drives up interest rates — would harm the economy. Their success in eliminating the primary deficit brought yields on the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond down from 8% to 4%.

In Clinton’s heyday, the Federal Reserve was limited in its ability to influence the 10-year Treasury interest rate. Its monetary interventions primarily targeted the federal-funds rate — the interest rate that banks charge each other on overnight transactions. But in 2002, Ben Bernanke advocated that the Fed “begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer-maturity Treasury debt.” This amounted to a schedule of interest-rate price controls.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has succeeded in wiping out bond vigilantes using a policy called “quantitative easing,” whereby the Fed manipulates the price of Treasury bonds by buying and selling them on the open market. As a result, Treasury-bond yields are determined not by the free market, but by the Fed.

The combined effect of these forces — the regulatory impetus for banks to own Treasury bonds, the liquidity advantage Treasury bonds have in the eyes of large financial institutions, and the Federal Reserve’s manipulation of Treasury-bond market prices — means that interest rates on Treasury bonds no longer indicate the United States’ creditworthiness (or lack thereof). Meanwhile, indications that investors are growing increasingly concerned about the U.S. fiscal and monetary picture — and are in turn assigning more risk to “risk-free” Treasury bonds — are on the rise.

One such indicator is the decline in the share of Treasury bonds owned by outside investors. Since 2009, the share of U.S. Treasury securities owned by foreign entities has fallen from 33% to 25%, while the share owned by the Fed nearly quadrupled, from 5% to 20%. Put simply, foreign investors have been reducing their purchases of U.S. government debt, thereby forcing the Fed to increase its own bond purchases to make up the difference and prop up prices.

U.S. Federal Debt Increasingly Owned by the Fed

(Ownership share of Treasury securities since 2008)

Until and unless Congress reduces the trajectory of the federal debt, U.S. monetary policy has entered a vicious cycle from which there is no obvious escape. The rising debt requires the Treasury Department to issue an ever-greater quantity of Treasury bonds, but market demand for these bonds cannot keep up with their increasing supply. In an effort to avoid a spike in interest rates, the Fed will need to print new U.S. dollars to soak up the excess supply of Treasury bonds. The resultant monetary inflation will cause increases in consumer prices.

Those who praise the Fed’s dramatic expansion of the money supply argue that it has not affected consumer-price inflation. And at first glance, they appear to have a point. In January of 2008, the M2 money stock was roughly $7.5 trillion; by January 2020, M2 had more than doubled, to $15.4 trillion. As of July 2021, the total M2 sits at $20.5 trillion — nearly triple what it was just 13 years ago. Over that same period, U.S. GDP increased by only 50%. And yet, since 2000, the average rate of growth in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for All Urban Consumers — a widely used inflation benchmark — has remained low, at about 2.25%.

How can this be?

The answer lies in the relationship between monetary inflation and price inflation, which has diverged over time. In 2008, the Federal Reserve began paying interest to banks that park their money with the Fed, reducing banks’ incentive to lend that money out to the broader economy in ways that would drive price inflation. But the main reason for the divergence is that conventional measures like CPI do not accurately capture the way monetary inflation is affecting domestic prices.

In a large, diverse country like the United States, different people and different industries experience price inflation in different ways. The fact that price inflation occurs earlier in certain sectors of the economy than in others was first described by the 18th-century Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon. In his 1730 Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General, Cantillon noted that when governments increase the supply of money, those who receive the money first gain the most benefit from it — at the expense of those to whom it flows last.

In the 20th century, Friedrich Hayek built on Cantillon’s thinking, observing that “the real harm [of monetary inflation] is due to the differential effect on different prices, which change successively in a very irregular order and to a very different degree, so that as a result the whole structure of relative prices becomes distorted and misguides production into wrong directions.”

In today’s context, the direct beneficiaries of newly printed money are those who need it the least. New dollars are sent to banks, which in turn lend them to the most creditworthy entities: investment funds, corporations, and wealthy individuals. As a result, the most profound price impact of U.S. monetary inflation has been on the kinds of assets that financial institutions and wealthy people purchase — stocks, bonds, real estate, venture capital, and the like.

This is why the price-to-earnings ratio of S&P 500 companies is at record highs, why risky start-ups with long-shot ideas are attracting $100 million venture rounds, and why the median home sales price has jumped 24% in a single year — the biggest one-year increase of the 21st century. Meanwhile, low- and middle-income earners are facing rising prices without attendant increases in their wages. If asset inflation persists while the costs of housing and health care continue to grow beyond the reach of ordinary people, the legitimacy of our market economy will be put on trial.

Bitcoin vs. Treasury bonds

Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous inventor of Bitcoin, hoped private currencies would directly compete with the U.S. dollar and other fiat currencies. But bitcoin does not have to replace everyday cash transactions to transform global finance. Few people may pay for their morning coffee with bitcoin, but it is also rare for people to purchase coffee with Treasury bonds or gold bars. Bitcoin is competing not with cash, but with these latter two assets, to become the world’s premier long-term store of wealth.

The primary problem bitcoin was invented to address — the devaluation of fiat currency through reckless spending and borrowing — is already upon us. If Biden’s $3.5 trillion spending plan passes Congress, the national debt will rise further. Someone will have to buy the Treasury bonds to enable that spending.

Yet as discussed above, investors are souring on Treasurys. On June 30, 2021, the interest rate for the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond was 1.45%. Even at the Federal Reserve’s target inflation rate of 2%, under these conditions, Treasury-bond holders are guaranteed to lose money in inflation-adjusted terms. One critic of the Fed’s policies, MicroStrategy CEO Michael Saylor, compares the value of today’s Treasury bonds to a “melting ice cube.” Last May, Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates and a former bitcoin skeptic, said, “personally, I’d rather have bitcoin than a [Treasury] bond.” If hedge funds, banks, and foreign governments continue to decelerate their Treasury purchases, even by a relatively small percentage, the decrease in demand could send U.S. bond prices plummeting.

If that happens, the Fed will be faced with the two unpalatable options described earlier: allowing interest rates to rise, or further inflating the money supply. The political pressure to choose the latter would likely be irresistible. But doing so would decrease inflation-adjusted returns on Treasury bonds, driving more investors away from Treasurys and into superior stores of value, such as bitcoin. In turn, decreased market interest in Treasurys would force the Fed to purchase more such bonds to suppress interest rates.

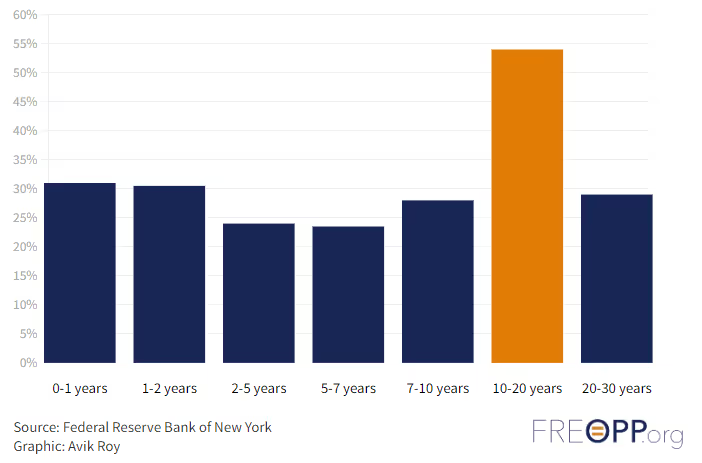

Fed Ownership of Treasury Securities, July 2021

(As a percentage of outstanding, by maturity)

From an American perspective, it would be ideal for U.S. Treasury bonds to remain the world’s preferred reserve asset for the foreseeable future. But the tens of trillions of dollars in debt that the United States has accumulated since 1971 — and the tens of trillions to come — has made that outcome unlikely.

It is understandably difficult for most of us to imagine a monetary world aside from the one in which we’ve lived for generations. After all, the U.S. dollar has served as the world’s leading reserve currency since 1919, when Britain was forced off the gold standard. There are only a handful of people living who might recall what the world was like before then.

Nevertheless, change is coming. Over the next 10 to 20 years, as bitcoin’s liquidity increases and the United States becomes less creditworthy, financial institutions and foreign governments alike may replace an increasing portion of their Treasury-bond holdings with bitcoin and other forms of sound money. With asset values reaching bubble proportions and no end to federal spending in sight, it’s critical for the United States to begin planning for this possibility now.

Bitcoin and the U.S. government

Unfortunately, the instinct of some federal policymakers will be to do what countries like Argentina have done in similar circumstances: impose capital controls that restrict the ability of Americans to exchange dollars for bitcoin in an attempt to prevent the digital currency from competing with Treasury's. Yet just as Nixon’s 1971 closure of the gold window led to a rapid flight from the dollar, imposing restrictions on the exchange of bitcoin for dollars would confirm to the world that the United States no longer believes in the competitiveness of its currency, accelerating the flight from Treasury bonds and undermining America’s ability to borrow.

A bitcoin crackdown would also be a massive strategic mistake, given that Americans are positioned to benefit enormously from bitcoin-related ventures and decentralized finance more generally. Around 50 million Americans own bitcoin today, and it’s likely that Americans and U.S. institutions own a plurality, if not the majority, of the bitcoin in circulation — a sum worth hundreds of billions of dollars. This is one area where China simply cannot compete with the United States, since Bitcoin’s open financial architecture is fundamentally incompatible with Beijing’s centralized, authoritarian model.

In the absence of major entitlement reform, well-intentioned efforts to make Treasury bonds great again are likely doomed. Instead of restricting bitcoin in a desperate attempt to forestall the inevitable, federal policymakers would do well to embrace the role of bitcoin as a geopolitically neutral reserve asset; work to ensure that the United States continues to lead the world in accumulating bitcoin-based wealth, jobs, and innovations; and ensure that Americans can continue to use bitcoin to protect themselves against government-driven inflation.

Establish a regulatory grace period for digital assets. To begin such an initiative, federal regulators should make it easier to operate cryptocurrency-related ventures on American shores. As things stand, too many of these firms are based abroad and closed off to American investors simply because outdated U.S. regulatory agencies — the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Treasury Department, and others — have been unwilling to provide clarity as to the legal standing of digital assets. For example, the SEC has barred Coinbase from paying its customers’ interest on their holdings while refusing to specify which rules Coinbase has violated. Similarly, the agency has refused to approve Bitcoin exchange-traded funds (ETFs) without specifying standards for a valid ETF application. Congress should implement SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce’s recommendations for a three-year regulatory grace period for decentralized digital tokens and assign to a new agency the role of regulating digital assets.

Establish rational tax reporting rules. Second, Congress should clarify poorly worded legislation tied to a recent bipartisan infrastructure bill that would drive many high-value crypto businesses, like bitcoin-mining operations, overseas. The bill mandates that all cryptocurrency “brokers” must report the names, addresses, and trading activities of those it interacts with, but defines “broker” to include any service “effectuating transfers of digital assets on behalf of another person,” overbroad language that effectively makes it illegal for innovators to develop ways to automate digital financial transactions, and abolishes a number of consensus algorithms essential to blockchain technology.

Create a U.S. strategic bitcoin reserve. Third, the Treasury Department should consider replacing a fraction of its gold holdings — say, 10% — with bitcoin. This move would pose little risk to the department’s overall balance sheet, send a positive signal to the innovative blockchain sector, and enable the United States to benefit from bitcoin’s growth. If the value of bitcoin continues to appreciate strongly against gold and the U.S. dollar, such a move would help shore up the Treasury and decrease the need for monetary inflation.

Prohibit a centralized U.S. virtual currency. Finally, when it comes to digital versions of the U.S. dollar, policymakers should follow the advice of Friedrich Hayek, not Xi Jinping. In an effort to increase government control over its monetary system, China is preparing to unveil a blockchain-based digital yuan at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. Jerome Powell and other Western central bankers have expressed envy for China’s initiative and fret about being left behind. But Americans should strongly oppose the development of a central-bank digital currency (CBDC). Such a currency could wipe out local banks by making traditional savings and checking accounts obsolete. What’s more, a CBDC-empowered Fed would accumulate a mountain of precise information about every consumer’s financial transactions. Not only would this represent a grave threat to Americans’ privacy and economic freedom, it would create a massive target for hackers and equip the government with the kind of censorship powers that would make Operation Choke Point look like child’s play.

Congress should ensure that the Federal Reserve never has the authority to issue a virtual currency. Instead, it should instruct regulators to integrate private-sector, dollar-pegged “stablecoins” — like Tether and USD Coin — into the framework we use for money-market funds and other cash-like instruments that are ubiquitous in the financial sector.

In the best-case scenario, the rise of bitcoin will motivate the United States to mend its fiscal ways. Much as Congress lowered corporate-tax rates in 2017 to reduce the incentive for U.S. companies to relocate abroad, bitcoin-driven monetary competition could push American policymakers to tackle the unsustainable growth of federal spending. While we can hope for such a scenario, we must plan for a world in which Congress continues to neglect its essential duty as a steward of Americans’ wealth.

The good news is that the American people are no longer destined to go down with the Fed’s sinking ship. In 1971, when Washington debased the value of the dollar, Americans had no real recourse. Today, through bitcoin, they do. Bitcoin enables ordinary Americans to protect their savings from the federal government’s mismanagement. It can improve the financial security of those most vulnerable to rising prices, such as hourly wage earners and retirees on fixed incomes. And it can increase the prosperity of younger Americans who will most acutely face the consequences of the country’s runaway debt.

Bitcoin represents an enormous strategic opportunity for Americans and the United States as a whole. With the right legal infrastructure, the currency and its underlying technology can become the next great driver of American growth. While the 21st-century monetary order will look very different from that of the 20th, bitcoin can help Americans maintain their economic leadership for decades to come.

.svg)