Bitcoin May Protect Against a Loss of Federal Reserve Independence

Bitcoin emerges as a powerful hedge against threats to Federal Reserve independence as political pressures intensify and federal debt reaches historic levels.

In The Case for Bitcoin as a Reserve Asset, I previously discussed bitcoin’s role as an emerging reserve asset, providing some protection against geopolitical risks, sanctions, and bank failures. In this blog post, I discuss whether bitcoin might provide an additional type of protection—against a loss of Federal Reserve independence.

Unlike the US dollar—whose supply expands and contracts as the Federal Reserve attempts to stabilize inflation—Bitcoin’s total quantity in circulation is capped, with prices permitted to fluctuate freely. Because the two assets represent completely different monetary philosophies, a loss of confidence in one system could plausibly have spillover effects on the value of the alternative system. This blog tests that hypothesis. First, I discuss the history of Federal Reserve independence; then I summarize recent debates about curtailing that independence; and lastly I explain my empirical findings regarding the relationship of bitcoin to Fed independence.

Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913 to promote financial stability after a series of banking panics in the late 1800s and early 1900s.1 The Federal Reserve System is comprised of regional Reserve Banks and a Board in Washington, DC. The Federal Reserve Board Governors sit on the interest rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) along with an alternating subset of the regional Reserve Bank presidents. The Governors are appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate, serve staggered 14-year terms, and may only be fired by the President “for cause”—all institutional features designed to insulate the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy decision-making from political interference. The President also appoints one of the Governors to be Chairman of the Board for a 4-year term.

The extent to which the Fed has acted independently of the Executive Branch has varied over time. During World War I, the Federal Reserve helped the Federal Government issue Treasury certificates and war bonds by providing low-interest loans to commercial banks to facilitate the banks’ purchase of government debt.2 During World War II, the Fed pegged short-term interest rates at 0.375 percent and long-term rates at 2.5 percent in order to finance the war.3 In part due to the Fed’s monetization of war debt, cumulative inflation between 1945 and 1951 was 44%.4 As a result of the FOMC’s concern about high inflation, the residual wartime collaboration between the US Treasury and Fed ended in March 1951 with an “accord with respect to debt management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose and to assure the successful financing of the government's requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt.”5,6 The principles of the 1951 Treasury-Fed Accord continue to underpin modern Fed independence.

When setting interest rates, the FOMC’s statutory objective is to maintain “price stability, maximum employment, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Historically, the FOMC has considered the third objective—moderate long-term interest rates—to be a consequence of accomplishing the first two objectives, so the FOMC has focused on achieving its first two goals, the so-called “dual mandate:” price stability and maximum employment.7

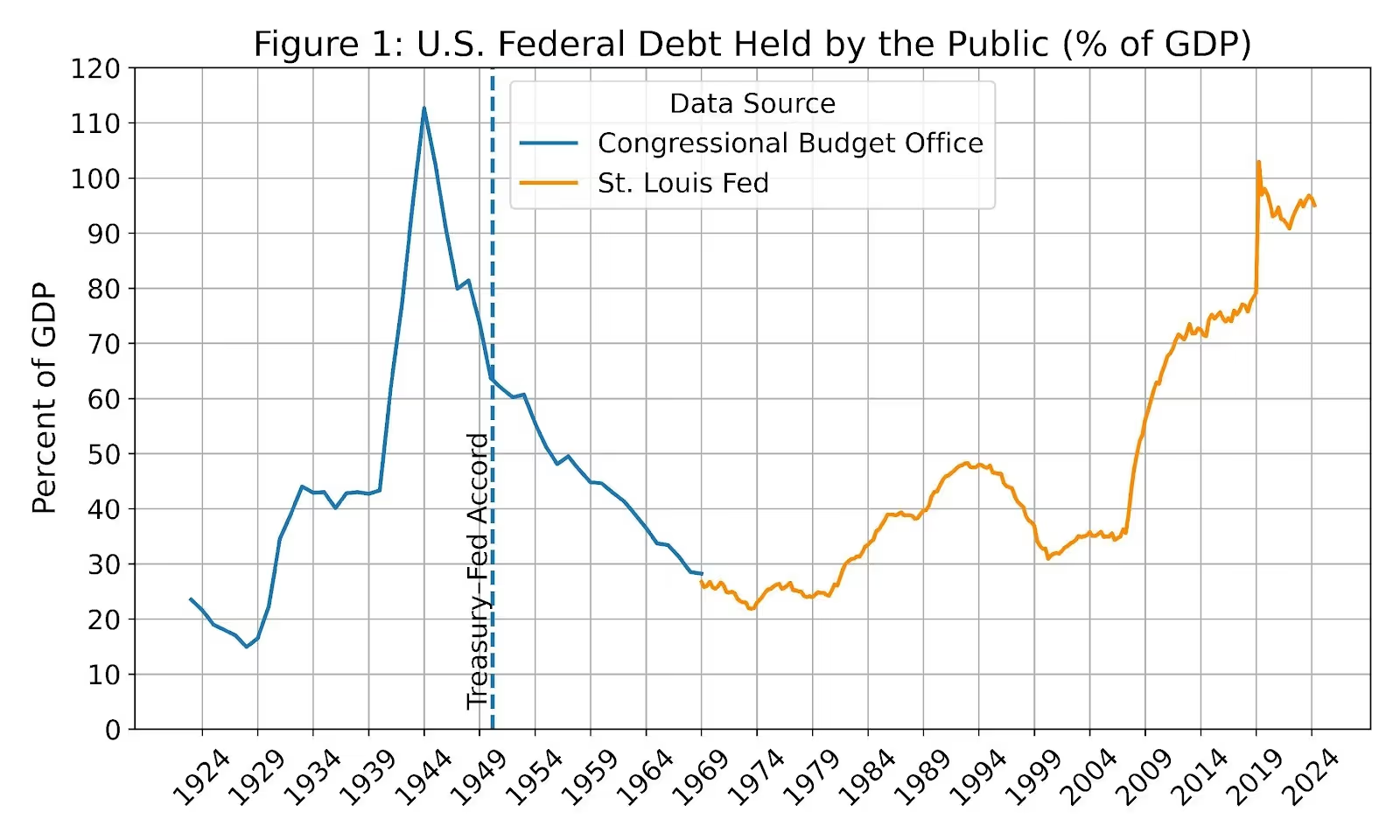

Today, the FOMC faces a dilemma. Federal debt held by the public has reached levels last seen during World War II (see Figure 1). If fiscal deficits remain large and the economy overheats, the resulting inflationary pressure could force the FOMC to raise rates substantially. However, high interest rates would dramatically increase the government's debt servicing costs, potentially creating political pressure on the Fed to keep rates lower than price stability would require—a situation known as fiscal dominance.

Because the Federal Reserve last relinquished some of its independence when the nation needed to finance World War II, and federal debt has once again reached World War II levels, it is unsurprising that discussions about reducing the Fed’s independence have intensified. Historically, high post-World War II inflation greatly reduced the economic burden of war debt for the US government (while eroding the purchasing power of the patriotic savers who purchased war bonds!).

In 2025, Congress debated two proposals to limit the Federal Reserve’s independence, although neither ultimately became law. First, several Members have suggested revoking the Fed’s ability to pay interest on bank reserves, a tool that helps the FOMC implement monetary policy.8 Although intended to generate cost savings for the Treasury, the proposal would likely have minimal long-run net effect on the federal budget because the Fed would need to sell some of its Treasuries to banks in order to maintain control over short-term interest rates, and the Treasury's interest expense remains the same regardless of whether banks hold reserves at the Fed or banks hold Treasury securities directly.9,10 Congress also proposed to cut salaries for some of the Federal Reserve Board’s employees, an action that would limit the Board’s power specified in 12 U.S.C. § 248(l) to set those salaries independently of the rest of the federal government.11

President Trump also took action against the Federal Reserve in 2025. The President attempted to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook based on allegations of mortgage fraud, and he has publicly debated whether to fire Chairman Jerome Powell. In one notable instance on July 15, 2025, President Trump reportedly discussed firing Chair Powell in a meeting with House Republicans, at which he presented the lawmakers with a draft letter firing Powell.12,13 No President has ever fired a Fed Governor or Chairman before. Financial markets probably perceive that a Presidential firing of the Fed Chairman would represent a direct challenge to Federal Reserve independence, because the Chairman leads FOMC meetings and is the primary spokesman for the Fed’s monetary policy.

Linking bitcoin to Fed independence requires identifying a proxy variable for the intensity of political pressure on the central bank. Polymarket, an online prediction market, provides exactly that: a market on the question of whether Jerome Powell would cease to be Chair of the Federal Reserve for any period of time in 2025.14 This question encompasses a range of scenarios, including the possibility that Powell might die in office, resign, be impeached by Congress, or be fired by the President. Even if Powell is subsequently reinstated by federal courts, a Presidential firing that at least temporarily removes Powell from office counts toward the market’s definition. Powell has not expressed any interest in resigning before the expiration of his term as Chair, nor has he had any major health incidents, so I attribute changes in the Polymarket probability to shifts in the likelihood of Powell being fired by the President. As of December 15, 2025, this market has had over $11.5 million of trading volume.

Academic researchers have previously used this particular Polymarket question to assess the likely effect of the Chairman’s firing on fiat assets.15 Tailard and Zeng (2025) examined the changes in the Polymarket probability on July 16, 2025 when major news outlets reported the aforementioned July 15 meeting between the President and Republican lawmakers, at which the President discussed firing Powell. After the publication of these press reports, the Polymarket firing probability sharply increased, but the probability subsequently declined after President Trump publicly stated during a White House Q&A two hours later that it was “highly unlikely” he would fire Powell.

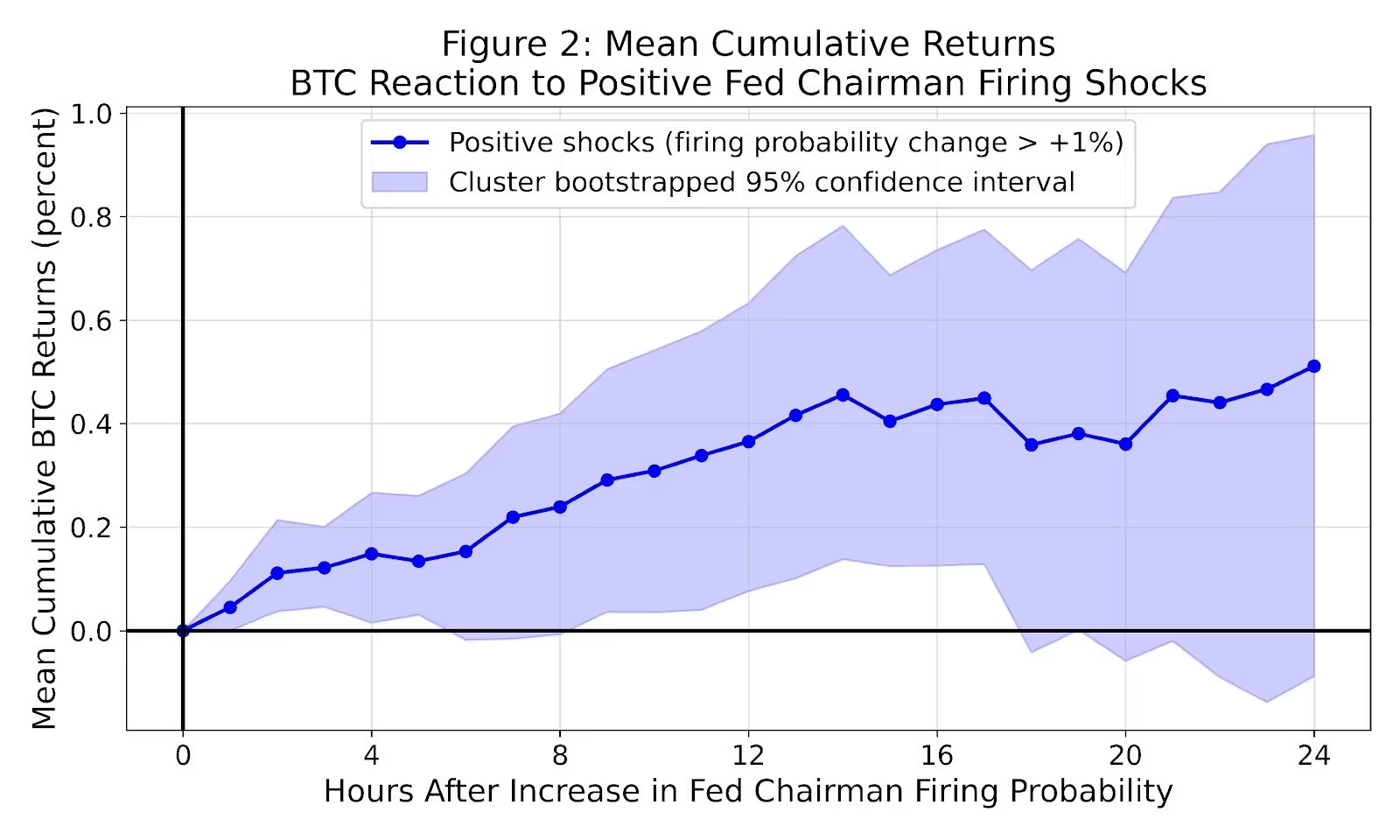

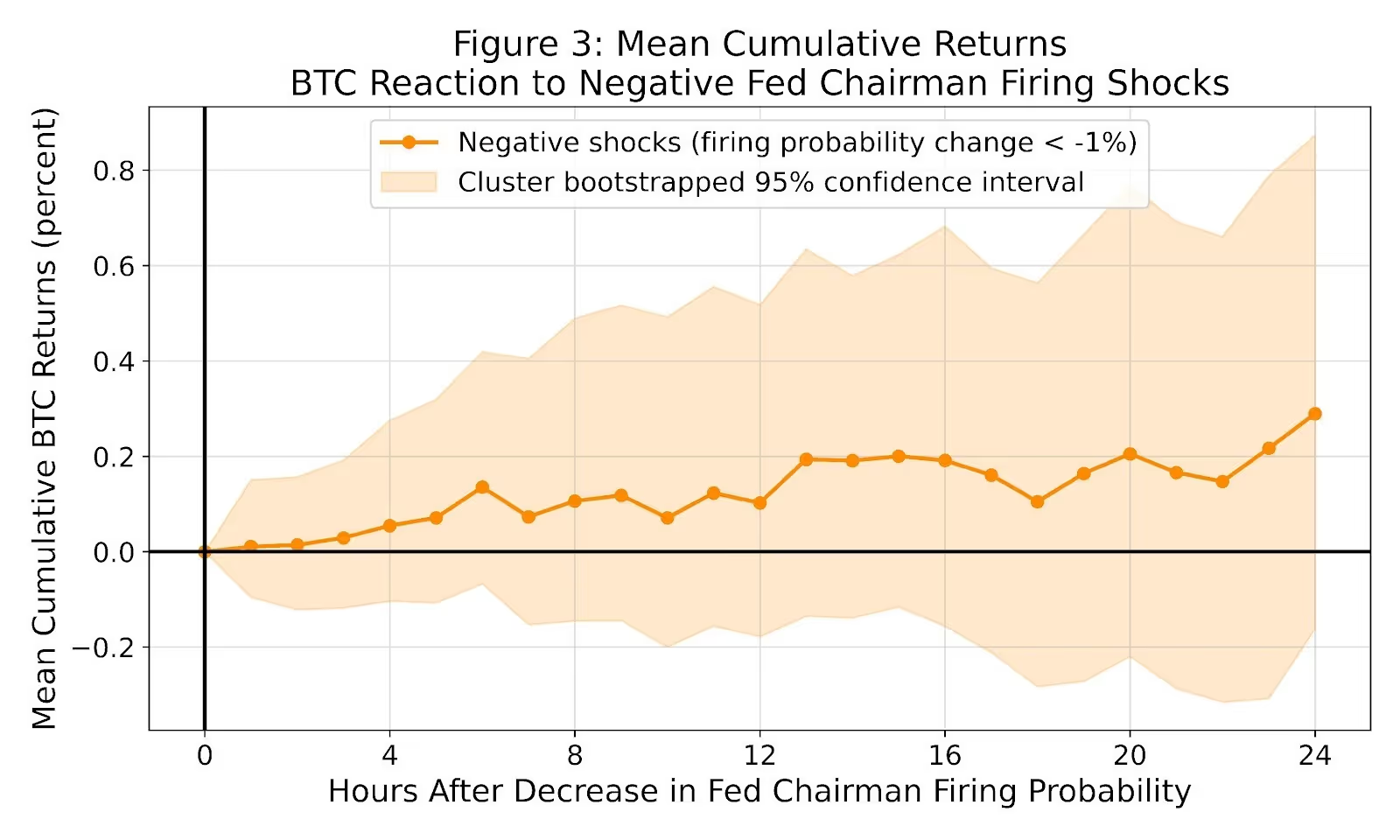

This study differs from that of Tailard and Zeng (2025) by adding bitcoin to the analysis and examining all hourly changes in the Polymarket probability that exceed one percentage point in either direction. By considering multiple episodes between January 30, 2025 and November 11, 2025, this analysis evaluates additional data and attempts to detect longer-term persistence in the firing probability’s effect on bitcoin.

In total, my sample includes 84 incidents when the hourly Polymarket probability increased by at least one percentage point, and 79 incidents when the hourly Polymarket probability declined by at least one percentage point. Some of the 24-hour windows around these incidents overlap with each other, so I account for this clustering in my confidence interval calculations. Among probability shifts, the average increase and decrease were nearly identical at 1.5 percentage points each.

My main finding is that Bitcoin’s price rises in the hours following increases in the Polymarket firing probability, with the mean cumulative effect peaking about 14 hours later. The increase in bitcoin’s price is statistically significant during 14 of the first 17 hours (Figure 2). However, the effect is not symmetric: decreases in the Polymarket firing probability appear to have no statistically significant effect on bitcoin’s price at all (Figure 3). Taken together, these results suggest that trust in the Fed’s independence can dissipate quickly, but the trust takes a longer time to rebuild.

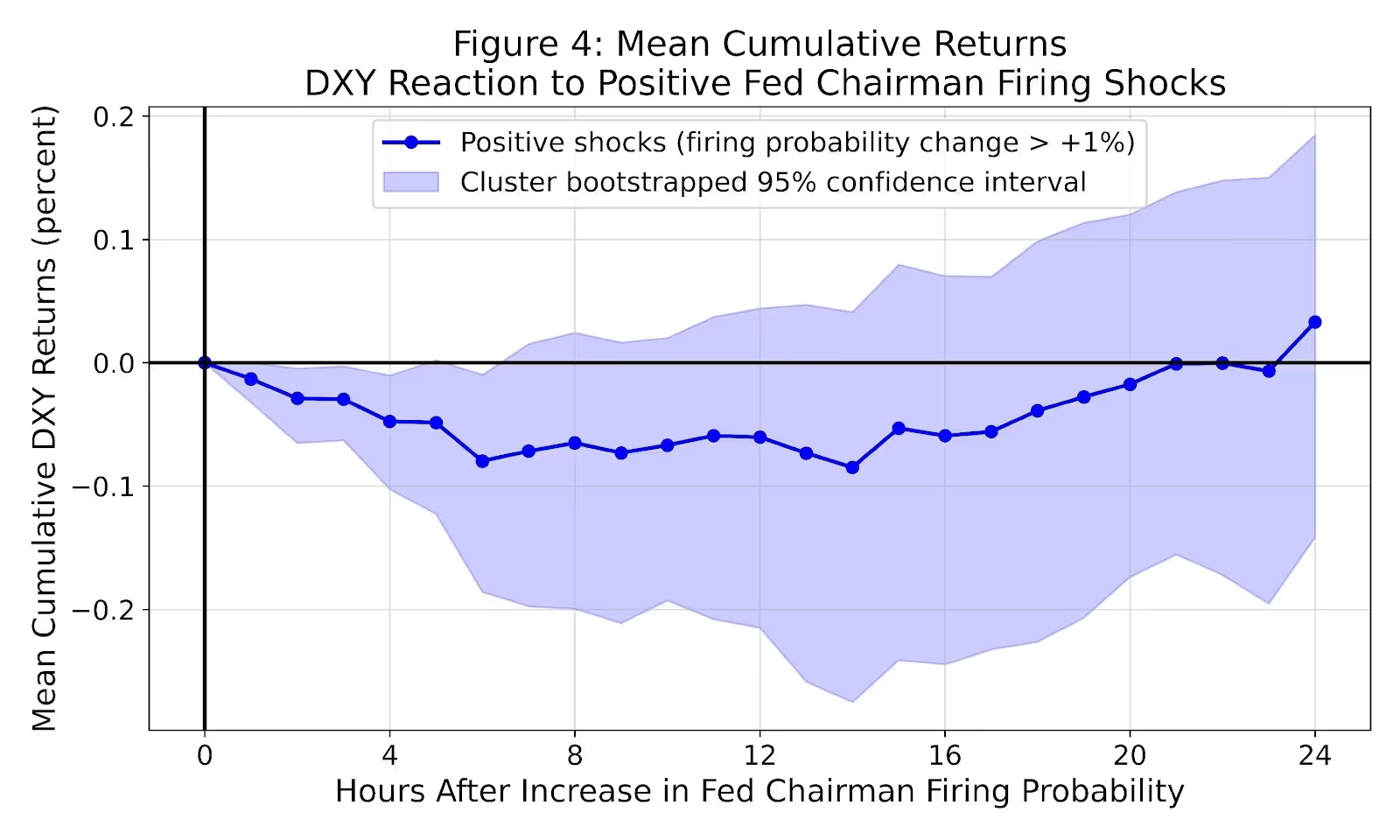

To investigate whether US dollar depreciation explains the bitcoin price increase, I also repeated the analysis using the US dollar index. I found that the US dollar does depreciate following increases in the firing probability (Figure 4), and the effect is statistically significant up to 6 hours following the firing probability increase. However, the magnitude of the US dollar depreciation is about half the estimated increase in bitcoin’s price at the 6-hour mark, indicating that investors perceive bitcoin to be a stronger hedge in this context relative to fiat foreign currencies.

Extrapolating from these findings, a sudden and unexpected firing of Powell could plausibly lead to a bitcoin price increase averaging around 10 percent within 6 hours, although this projection is highly uncertain. If the Federal Reserve's credibility remains weakened by earlier firing probability increases, the effect could be more moderate. Regarding the US dollar, my results indicate that an unanticipated firing could lead to a peak depreciation of approximately 4.8 percent. My estimate aligns closely with the 3-4 percent dollar depreciation projected by Tailard and Zeng (2025), particularly because the apparent persistence of effects from previous events suggests that 4.8 percent may be an upper bound. But, if federal courts permitted a Presidential firing of Powell for minimal or no cause, the effects on both bitcoin and the dollar might be more extreme.

This analysis reveals that bitcoin functions as a hedge against a reduction in Fed independence, with its price rising significantly following increases in the probability of Chairman Powell's firing. The asymmetric response—where bitcoin gains ground when firing risks increase but does not decline when those risks subside—suggests that confidence in central bank independence erodes quickly but rebuilds slowly. Meanwhile, the US dollar's more modest depreciation indicates that while currency markets react, bitcoin appears to offer a unique alternative for investors seeking protection against political interference with monetary policy.

These findings have important implications as federal debt approaches World War II levels and political pressures on the Federal Reserve intensify. But today's fiscal challenges differ fundamentally from those of the 1940s. Lowering interest rates and triggering higher inflation will not fix today's high deficits because the entitlement programs driving current deficit spending are largely inflation-adjusted. Unlike World War II, the costs of Social Security and Medicare are not temporary; they reflect an open-ended, inflation-adjusted promise to an aging population. Moreover, limiting Fed independence would likely increase long-term interest rates as investors demand higher risk premiums for holding US debt, even if political pressure forces the Fed to suppress short-term rates. While inflation and lower short-term interest rates might temporarily erode the existing debt stock, ongoing deficits and higher long-term rates would quickly rebuild it. Inflation would therefore fail to reduce the real burden of federal obligations while simultaneously undermining the Federal Reserve's credibility.

Bitcoin may play an increasingly important role in portfolios, particularly for those concerned about the erosion of central bank autonomy. Whether bitcoin ultimately fulfills this role will depend not only on the level of Fed independence, but also on how courts, Congress, and future administrations navigate the delicate balance between democratic accountability and the institutional insulation necessary to implement effective monetary policy.

Endnotes:

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/feds-formative-years

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/feds-role-during-wwi

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/treasury-fed-accord

- https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator/consumer-price-index-1913-

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/treasury-fed-accord

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/wwii-to-the-treasury-fed-accord

- https://www.axios.com/2025/09/17/trump-fed-miran-third-mandate

- https://www.rickscott.senate.gov/2025/7/sens-rick-scott-ted-cruz-lead-bill-to-stop-federal-reserve-from-wasting-1-trillion-paying-interest-on-bank-reserves

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-would-happen-if-congress-repealed-the-feds-authority-to-pay-interest-on-reserves/

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/iorb-faqs.htm

- https://www.bankingdive.com/news/one-big-beautiful-bill-senate-banking-cfpb-funding-fed-non-monetary-policy-pay-ofr-scott-warren/750173/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-asked-gop-lawmakers-if-he-should-fire-jerome-powell-sources/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/16/us/politics/trump-powell-firing-letter.html

- https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0895330041371321

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5436816

Disclaimer: All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the US Government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US Government authentication of information or endorsement of the author's views.

.svg)