What Does U.S. Free Banking Tell Us About Stablecoins?

Exploring lessons from America’s free banking era for the future of stablecoins

United States’ free banking often is brought up as an example of how stablecoins are liable to work. This occurs in regulatory and political contexts and sometimes in academic articles. Free banking often is asserted to have suffered from irremediable problems that would recur with stablecoins, and to have been an era of “wildcat banks.” U.S. federal government currency is viewed as having been the solution to problems with free banking. A similar conclusion often is inferred: central bank digital currency would be preferable to private stablecoins.

Michael Held, Executive Vice President and General Counsel at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York asserted in a speech at the Bank for International Settlements on December 3, 2019:

“By the 1860s, Congress was fed up with the free banking system. … It is hard not to see certain parallels between today’s digital currencies and the bank notes issued during the wildcat era.”

Lael Brainard, a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve at the time, suggested in a speech to the Consensus Conference by CoinDesk on May 24, 2021 that:

“Indeed, the period in the nineteenth century when there was active competition between issuers of private paper banknotes in the United States is notorious for inefficiency, fraud, and instability in the banking system. It led to the need for a uniform form of money backed by the national government.”

Elizabeth Warren, a U.S. Senator, claimed in a hearing on digital currencies on June 9, 2021 that:

“… [T]his is not the first time that we have had private-sector alternatives to the dollar. … In the 19th Century, ‘wildcat notes’ were issued by banks without any underlying assets. And eventually the banks that issued these notes failed and public confidence in the banking system was undermined.”

The Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) Annual Economic Report for 2025 goes into more detail about the deficiencies of stablecoins while bringing up the similarity to private banknotes during the Free Banking Era:

“As digital bearer instruments on borderless public blockchains, stablecoins have been the go-to choice for illicit use to bypass integrity safeguards.

Stablecoins also fare poorly on singleness …. As digital bearer instruments, they lack the settlement function provided by the central bank. Stablecoin holdings are tagged with the name of the issuer, much like private banknotes circulating in the 19th century Free Banking era in the United States. As such, stablecoins often trade at varying exchange rates, undermining singleness.”

“Singleness” is a term used by regulators and means that different notes with the same par, or face, value trade at exactly that par value. For example, singleness implies that a $10 bill trades at a value of $10 for any other $10 unit of currency in use. A $10 bill issued by the federal government is always worth the same as any other $10 bill issued by the government. Similarly, “singleness” suggests that a $10 check drawn from a bank or $10 private banknote should trade without any discount or premium for a $10 bill issued by the government. It is worth mentioning that bank checks in the United States often were paid with a discount until the Monetary Control Act of 1980. The holder of a check for $10 receives $10 now.

Some academic literature echoes these comments, especially those mentioned in the BIS discussion. Gary B. Gorton and Jefferey Y. Zhang wrote a paper on “Taming Wildcat Stablecoins” published in 2024. The original draft of this paper was written while Zhang was a senior attorney at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. In the published paper, their main complaint about wildcat banks is not that they failed due to fraud, but a more technical one (p. 944):

“Bank failures were not due to wildcat banking as has often been alleged. … [W]hile the market was an efficient market in the sense of financial economics, varying discounts made actual transactions (and legal contracting) very difficult. In other words, it was not economically efficient. There was constant haggling and arguing over the value of notes in transactions. Private banknotes were hard to use in transactions.”

This complaint echoes the BIS under the term “singleness,” despite the title suggesting “wildcat stablecoins.”

What was free banking in the U.S. Free Banking Era and what can it tell us about stablecoins? Was it an era of “wildcat banking?” (Details underlying the following observations and more can be found in Dwyer, “Wildcat Banking, Banking Panics, and Free Banking in the United States,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, December 1996.)

The Free Banking Era in the United States began in 1837 when the state of Michigan passed a law creating free banks in Michigan. The era ended when the U.S. government levied a 10 percent annual tax on state banknotes in 1865 to eliminate state banknotes.

All banks in this period had state charters. The federal government chartered the First and Second Banks of the United States, with the Second Bank’s federal charter expiring in 1836. There were no other federally chartered banks until the National Banking Act of 1863 created national banks. Before free banks, chartered state banks had existed for years, obtaining charters from the state legislature in the state in which they operated. Each of these charters required a specific state law creating the bank. Free banking laws required no such special law, but instead required applicants to apply to the state’s bank regulator for a bank charter after meeting certain criteria such as being of good character and putting up sufficient capital to start a bank. These free banking laws are similar to general incorporation laws introduced about the same time, and which still exist. General incorporation laws require a corporation’s founders and the corporate structure to meet certain criteria; if those criteria are met, then a charter is granted. This is very different from banking today in which a charter can be denied, for example, if the regulator concludes the bank might fail.

The term “wildcat banking” likely arose from the Michigan experience with free banking. Michigan was a frontier state in 1837 and the suggestion was that banks, instead of being located in towns, were located “where the wildcats roamed.” Why would they pick such locations?

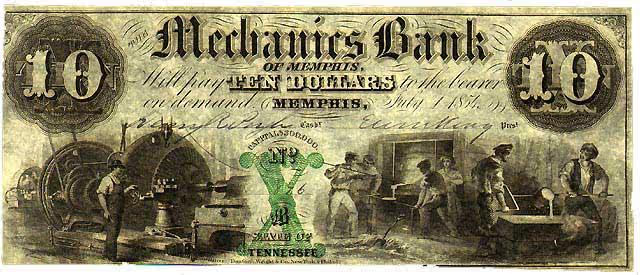

Banks issued notes which were currency that could be used in hand-to-hand exchanges outside the bank. These notes were liabilities of the bank. The figure below shows an example. Banks were required to promise to redeem on demand their notes for the value of gold or silver equivalent to the face value of the note. A remote location would reduce the frequency with which the bank’s notes would return to the bank to be redeemed. Less frequent redemption would allow the bank to hold less gold or silver instead of an interest-bearing asset. Unfortunately for Michigan, there was a nationwide suspension of payments by banks shortly after Michigan passed the free banking law and Michigan followed suit. As a result, banks did not have to redeem their notes and many new free banks sprouted up. Those banks subsequently failed when redemption resumed, and Michigan banknotes got a bad reputation, so much so that Michigan repealed its free banking law.

Figure 1: Example of a free banknote

Source: https://en.numista.com/catalogue/note205645.html

Other states, although not all, passed free banking laws later. And these laws generally, if not always, required that banks be located in towns with some minimum population to make it easier to redeem notes and make sure the bank held some gold or silver. Legislators learned.

Fraud did occur in the Free Banking Era. It occurs today and will continue in the future, but a typical bank was not fraudulent. Even courts in the day generally had positive opinions about free banks.

There were failures. Banks were not required to hold 100 percent reserves in gold or silver. Instead, they deposited marketable bonds with the state banking regulator, and the regulator would issue notes equal to the lesser of the market or par value of the bonds. The banks received the interest on these marketable bonds.

The most severe failures occurred at the start of the Civil War when the value of Southern state bonds fell. Free banks held substantial amounts of these bonds.

Why would free banks hold Southern bonds? State bonds during this period generally had market values greater than their par value (final redemption value). Southern bonds had smaller premia and therefore allowed a bank to issue more notes than Northern state bonds. While U.S. bonds might have been attractive and were allowed in many states, the federal government had little debt in this period. While short-term bonds would have had less price risk, bonds issued in this period were long term.

Another issue mentioned in the quotes above is the discount on a bank’s notes away from the bank. They did have such discounts, and it is easy to see why. Banks were permitted to have only one office, notes had to be redeemed in person at that office, and transportation was expensive. This was the era of railroad expansion; construction of the first railroad in the United States began in Maryland in 1828. As a result, there were discounts for notes away from the bank due to the time and expense required to return them to the bank. There also were discounts because it took time to receive information about banks at some distance. The first telegraph message was sent from Baltimore to Washington D.C. in 1844.

Most stablecoins have been backed by reserves, in some ways similar to the free banks, but some have been algorithmic stablecoins. Algorithmic stablecoins which have no reserves, such as Luna, relied on a belief that the price would return to the face value. This never made much sense as a long-term guarantee of value. There always is a non-zero probability that holders will decide that the price will not return to the face value. When that happens, and it will almost surely, the algorithmic stablecoin falls from the face value, never to return to it. That’s what happened to Luna.

The reasons for discounts in free banks’ notes prices do not apply to stablecoins with reserves. Stablecoins are digital. They can be redeemed almost instantaneously at zero cost depending on the precise contract between the issuer and holders. Once the GENIUS Act takes effect, information about the value of reserves held by U.S. stablecoin issuers will become readily available. By requiring full audits, the law will reinforce market confidence by ensuring transparency of reserves. The value of a marketable security can be known instantly anywhere in the world with an Internet connection. Arbitrage across exchanges located anywhere in the world keeps stablecoin prices in tight ranges everywhere.

Anyone who has followed the prices of stablecoins with reserves knows that the market prices deviate little from their face values. At the time of this writing, the price of Tether at coinmarketcap.com is $0.9998. The price of USDC is $0.9999. Sometimes the prices are above $1.00. Any deviations are short lived. Both prices were $1.00 by the time I wrote these sentences. This variation in prices is trivial and bears no relationship to the range of variation in the Free Banking Era. Hundredths of a penny are rounding errors even in a one-penny transaction.

The Free Banking Era is an interesting period for some of us and does have lessons about the economics of note-issuing banks. These lessons concern which assets are better, and which are worse. The history shows that the best-intentioned bank regulation can be helpful, or it can be detrimental. The antebellum era was a very different world than today’s and has little to add to understanding problems with stablecoins’ viability or efficiency due to information.

.svg)